Accountability and the inner work of leadership

Leadership gurus are often asked about the difference between management and leadership, and how to make the transition. My two answers: accountability, and inner work.

The perfect manager, but not yet a leader

Charlotte is an experienced and highly trained senior manager. She knows good management starts with herself, so she sets weekly goals, prioritizes, manages time well, keeps all her promises faithfully, has determination and courage when things get tough and keeps herself mentally and physically fit. She is exceptionally competent at managing her staff; they get constant (not annual) encouragement, support and feedback on their performance. She has a flair for organisation and delegation; her people feel trusted and empowered. The people that work for Charlotte collaborate, share information and learn from one-another because Charlotte insists they operate as a team and invests time in developing their team-working. Charlotte is exceptionally good at managing upward; she keeps her boss informed of progress and of possible breakdowns making it easier for her boss to co-ordinate and manage his team. Charlotte is a great team player and is well respected by her peers and by the other functions with which she interacts on a daily basis.

But Charlotte isn’t a leader and doing more of all those things that Charlotte does so competently won’t make her into one. Leadership is something different – and most managers never make the leap and become leaders. So what are the differences between leading and managing and what personal barriers stop managers making the leap? There are many, but here I would like to focus on one of the biggest: accountability.

Accountability separates managers from leaders

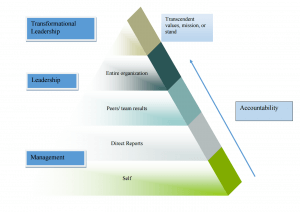

Many organisations use “accountability” synonymously with “role”, but it means much more than that. Furthermore, there are five levels of accountability (figure 1) most of which managers never reach. At school and college, we learn to be accountable for our own results, to produce high-quality work, on-time. Then we may become a manager, and we become accountable for the results that everyone who works for us produces. Many managers actually fail at this level. At one bank at which I worked, the top-team forever threw their hands in the air saying “our staff just aren’t up to delivering …”. They hadn’t yet made it to this second level of accountability. Good managers are accountable for what happens below them, but it is at the next, higher level of accountability that leadership really begins.

In school, we don’t normally see ourselves as accountable for everyone else’s homework or exam results. But at the next level of accountability, this is what is required! Everywhere in business, the individualistic mindset, inherited no doubt from our educational experience, persists. On high-functioning teams, each team member is accountable for the other team member’s results. Sports teams are a good example of this working – but in business, the story is more typically “my group are producing, I wish the others would sort themselves out”, or “my group are not producing, but I will keep this to myself until it sorts itself out”. Or worse, the “team” members actually compete with one-another for resources, or even foil each other’s plans. At one major airline, this kind of thinking meant they struggled with a small-scale restructuring for two years before finally giving up.

In practice this means support and challenge. Support is as it sounds. When the pressure is on, or the chips are down, the head of one unit does everything she can for their peer as if it were her own team struggling. Culture can get in the way here: some people are bad at asking for help, and some are poor at accepting when offered. Challenge can be tougher to pull off. It must be done compassionately, not “hey, get it together!” For example, “it looks to me as if you are having trouble playing your part… can you see why I might say that, and if so, how can I help?” Again culture can get in the way – in a heavily siloed culture, manager A may well tell manager B to get lost if the challenge is badly taken. It is their leader’s role to create the kind of culture where team members can view themselves as co-accountable and act accordingly.

However, don’t take my word for it – consider what it would be like on your team if everyone saw their accountability in this way. What would it make available in terms of support, collaboration, teamwork, and sharing of resources? It goes further: there are levels of accountability even higher than this. At the first three levels, managers were accountable for their own results, then their department’s results, then their peer-team’s results. Accountability was down or side-ways. At the next two levels, leaders take on upward accountability, even in roles without “position power” ordirect authority. Without authority or rewards to back them up they inspire those around them and above them to produce results.

While at PwC, I witnessed an example of the fourth level of accountability. A group of three 25-year old “intrapreneurs” (James Shaw, Amy Middleburg, and Fabio Sgaragli) had gained the ear of the global chairman and through taking on this level of accountability started PwC on a journey toward greater Corporate Social Responsibility. These young graduates had no political clout, organisational influence, or job experience. Through their leadership they were able gain the support of the Chairman of the largest professional services firm in the world, who birthed many firm-wide initiatives to examine the problem critically and develop both internal solutions, and client offerings. Few industries in the world are as innately conservative as the accountancy profession, yet the multi-million dollar initiatives spawned by this group were part of a major industry rethink about how to measure value.

The final level of accountability to a supra-organisational ideal, standard, or purpose – is rarer still. When Ghandi began to stand for the independence of India, he had none of traditional sources of power such as wealth or political influence. King was a black man in a part of the United States where blacks were legally and culturally treated as second class citizens. Both men stood for something far beyond their reach, and far beyond their political power. Yet their taking a stand actually became a source of their power.

At a more modest level, I had the privilege of coaching Graham, a 23 year old, 5’ 5”, extremely shy, Irish computer programmer several years ago. He was on a leadership development programme where leadership is taught through leading projects, not at fancy conference sites. Graham saw and was saddened by the plight of London’s homeless and took on raising £20,000 for CRISIS and building a statue of the number 2000 out of used clothing in London’s Battersea Park. The event drew huge crowds, reached its financial goals and was attended by major TV stations and newspapers. Throughout the entire project Graham had to confront his shyness, his age, the politics of homelessness and other barriers and was propelled only by his passion to make a difference and his vision. Now imagine what it would be like in your company if 23-year-olds were the kind of leader that Graham became – inspired, inspirational and able to surpass daunting obstacles.

Clearly we are talking about a different phenomenon from management. It has been accurately said that management is about efficient working within constraints; but leadership demands working beyond constraints. Management is about stability; leadership is about change. Management is about structure and systems; leadership is about people and direction.

Beyond accountability to whole-person leadership

So how do leaders produce the results for which they make themselves accountable? As can be seen, taking on the accountability is a source of power in itself. Just the act of standing for something great is inspirational, but there is more. Leaders operate in the dimensions of emotion and spirituality.

It is said that “great leaders inspire ordinary people to do great things in the face of adversity”. This makes leadership more than just a rational phenomenon – because inspiration and motivation are partly emotional. To be precise, inspiration could be called a mood. Inspiration and similar moods like vitality and excitement cause the world to be viewed in a certain way. These moods favour certain types of cognition, allow situations to be “framed” as opportunities; they open up new possibilities and pathways for action.

By contrast, moods like resignation, scepticism and anxiety focus thinking in other directions. Situations can appear as threats or problems. Pathways and possibilities are closed down. It is not that these moods are “bad”; they can be quite useful for avoiding risks or danger. But they do close-off situations, rather than open them up.

Accessing the moods and emotions of followers takes more than thinking, reasoning, and cognition. However well-argued a “business case” might be, just the numbers won’t inspire followers into action! To work within and influence in the domain of mood and emotion, leaders require what is popularly called emotional intelligence. That is the ability to observe, communicate and manage mood and emotion (especially their own). Sadly, this is something that our business environment and our culture have been hostile toward. This isn’t something soft like getting “in-touch with one’s feelings”, but it is having one’s own mood and emotion congruent and aligned with one’s speaking, and it is being able to produce a shift in the mood of a team, organisation, or even a country.

So accessing mood and emotion are essential, but spirituality!? By this, I don’t mean traditional, or New Age crystals. Spirituality doesn’t exclude those, but it can also be a 100% secular phenomenon. Spirituality is a search for meaning, purpose, and connectedness in life. It is the WHY of life? Why am I here? Is this what I am meant to do? What am I a part of? And everybody has it – it is part of being human.

Leaders cause followers to be “unstoppably” committed. But this kind of commitment exists only when there is a burning “why” that followers connect to. That is, a context for their activities that gives them bigger meaning and that is congruent with their values.

The oft-told parable of the three-stone cutters working side by side illustrates. The first, disenchanted, says “I’m carving stone”. The second, contented, says “I’m building a wall”. The third, inspired and glowing, says “I’m building a cathedral.” This is the spiritual realm of leadership – meaning, values, connectedness to something bigger; a bigger “why”. The power of this dimension is unquestionable. People are willing to go to war and die for ideals, purposes, beliefs that have little to do with actual needs. In fact Gandhi said, “such power as I possess for working in the political field is derived entirely from my experiments in the spiritual field.” All great leaders appeal to values. Thatcher appealed to material values and captured the hearts and votes of the growing British middle-class: home-ownership, individual self-determination, and the rights of capital over labour. Mandela appealed to values such as freedom, equality, human dignity, and democracy and provided much of his leadership of the change in South Africa from a jail cell. Jesus and Buddha appealed to values such as compassion and forgiveness – and we still talk about their leadership today.

Back in the business world, leaders tell followers what cathedrals they are building and why. Jack Welch is perhaps the most-toasted corporate leader of the 90s. His maxims: to be number 1 or 2 in all our markets1 , to be an organisation without walls, and to live and practice our corporate values in all we do. It used to be said at GE: “you can’t get fired here for not making your numbers, but you can get fired for not living the values.” This context setting provides a means of interpreting the external environment and supplies a set of principles through which decisions can be viewed. Furthermore, it gives followers some inspirational goals to aim at and to align around when there is dissent.

When you think about it, it makes sense. If we view human beings as rational, emotional, physical and spiritual – then effective leadership will have to access all of these domains. Managers tend to access only the rational dimension: analyzing, planning, strategizing, structuring, organizing and control. This is a good thing – I like my trains to run on-time. However, there is more to leadership than all that.

So why do we see so few leaders? Why do so few managers make the leap?

To be accountable at the higher levels, three things are essential. One, you can’t be in control, and second, you have to be prepared to fail, and third, you need to be “comfortable being uncomfortable”. Psychologically, these are very distressing indeed. It is much easier to play safe and stay in control and not fail, than to take risks, play big, and bet the farm on number 17.

Human beings and organisations full of them are too complex to control – the concept of management control was born of an era when things were slower moving and less complex. Some great financial institutions have lost hundreds of millions of dollars (such as Barings, Nat West and now Allied Irish) living in the fantasy that systems and procedures can control human beings.

Failing is something that is absolutely programmed out of us from the age of seven. As we get older, failures have bigger consequences (University results, A-level results) – so we are petrified of them. However, failure is part of leadership and would-be leaders who avoid failure at all costs never graduate from management to leadership.

The old sailing aphorism “in order to reach the farthest shores, it is first necessary to lose sight of the one you are departing” summarises the feeling of “comfortable being uncomfortable”. Since leadership is about change, and all change causes some discomfort, followers need to be comfortable being uncomfortable and leaders need to model this.

To lead change, leaders need to:

- step outside their comfort zone and stay there;

- manage their moods so they can manage the mood of their team;

- get in touch with their “source” (inspiration) so they can inspire followers;

- get clear about what their work means to them, so they can help followers create meaning;

- establish shared purpose and values, through becoming clear about their purpose and values;

- connect to something bigger than themselves, so they can connect followers to something bigger than themselves!

In summary, leaders need psychological and spiritual depth. But achieving this depth takes inner work. It takes a willingness to ask difficult questions of oneself – to ask “why”? To stretch followers and have them grow, it is essential that leaders stretch themselves and grow. Jack Welch’s former number two and now a CEO in his own right, Larry Bossidy, said “I can only change this company as quickly as I can change myself.”

But such thoughts are rare at the top of organisations. More often that not, the higher people go the more resistant to change they become – particularly when it involves personal change. It seems as if the higher people climb in their careers, the more afraid of falling they become. When I get called in to discuss leadership development, it is a rare leader indeed that says “Oh and by the way, you can start with me.” That kind of self-honesty and humility is what great leaders seem so rare.